From ancient times to the present day, veterinary care has advanced significantly. Many conditions that were once difficult or impossible to treat are now managed routinely—orthopedic surgery being a prime example. Despite these advances, orthopedics is still considered a specialized field within veterinary medicine, and many pet owners are not fully familiar with what it involves.

In this article, we take a closer look at veterinary orthopedics, breaking down the concepts and tools used to repair broken bones so they are easier to understand.

What Is Orthopedics?

The term orthopedics was coined by a French surgeon and originates from the Greek words “ortho-” meaning straight or correct and “-paidion” meaning child. This is because early orthopedic practice focused on correcting skeletal deformities in children, such as scoliosis and bowlegs.

However, orthopedic treatment has existed for much longer. Evidence suggests that fracture stabilization techniques may date back to ancient Egypt, where splints were found attached to mummies. During the Middle Ages—particularly in times of war—soldiers attempted to treat fractures using splints and basic immobilization techniques.

Modern orthopedics is a broad discipline encompassing all conditions related to the musculoskeletal system, including bones, muscles, joints, and ligaments. In human medicine, common orthopedic procedures include fracture repair, hip replacement, and arthroscopy.

As human medicine advanced, veterinary medicine followed closely—sometimes even leading the way. Historically, veterinary care focused mainly on working animals, especially horses, due to their susceptibility to limb injuries. With the rise of pet ownership during the Victorian era and the development of X-ray imaging, fluoroscopy, safer anesthesia, sterile techniques, antibiotics, and metal implants, veterinary orthopedics evolved into the advanced specialty it is today.

What Tools Do Veterinary Orthopedic Surgeons Use?

Orthopedic surgery is far more complex than simply “fixing” a broken bone. It requires specialized equipment, detailed planning, and a deep understanding of biomechanics.

Veterinary orthopedic surgeons must consider several key principles, including:

Restoring normal limb function as quickly as possible

Minimizing additional tissue damage

Understanding how weight-bearing forces affect bones and joints

Selecting the most appropriate fixation method

Diagnostic imaging—typically X-rays and sometimes CT scans—is almost always required before surgery.

Below are some of the most commonly used orthopedic tools.

Intramedullary Pins

Intramedullary pins are long metal rods inserted lengthwise into the medullary cavity (center) of a bone. They are commonly used to treat fractures of the femur, tibia, and ulna.

Their primary function is to align fracture fragments and resist bending forces. They can often be placed with minimal surgical exposure. However, intramedullary pins provide limited resistance to rotational and compressive forces, so they are frequently combined with plates or cerclage wires. In some cases, pins may migrate and protrude through the skin, causing pain and mobility issues.

Cerclage Wire

Cerclage wire is a flexible, malleable wire that can be shaped as needed. It is often wrapped around bones to prevent lateral movement and works especially well when combined with intramedullary pins.

When used with Kirschner wires, cerclage wire can apply tension or compression to guide bone alignment. Its disadvantages include the need for greater bone exposure and the risk of wire slippage, which may delay bone healing.

Kirschner Wires (K-Wires)

Kirschner wires are thin metal pins inserted into bone. They are particularly useful for joint fractures in young animals, where precise alignment is critical to prevent long-term joint problems.

K-wires are also used to reattach bone fragments that have been pulled away by tendons or ligaments. Often combined with cerclage wire in a tension band construct, K-wires can usually be removed after healing—unlike many other orthopedic implants.

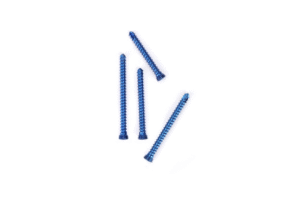

Orthopedic Screws

Orthopedic screws resemble household screws but are manufactured to much higher precision. Made from stainless steel or titanium, they are designed specifically for bone fixation.

Screws may be used to:

Hold bone fragments together (position or neutralization screws)

Compress fracture fragments tightly (lag or compression screws)

Some screws are designed to fit precisely into bone plates, while others can be used independently. Depending on the design, some screws require pre-drilling, while others are self-drilling or self-tapping. Orthopedic screws come in a wide range of sizes and shapes to suit different surgical needs.

Bone Plates

Bone plates are metal implants used in combination with screws to stabilize fractures, resist weight-bearing forces, and promote bone healing.

Properly applied plates restore anatomical alignment and allow early functional recovery. There are many types of bone plates, each available in multiple sizes. Surgeons often contour plates during surgery to achieve an exact fit.

Bone plates typically span the fracture and are fixed with screws on both sides. Some plates compress fracture fragments, while others primarily resist mechanical forces, especially when used alongside intramedullary pins. Because plates require significant exposure and precise placement, surgery times are longer and incisions larger.

External Fixators

External fixation systems stabilize fractures using pins inserted into bone and connected to a rigid frame outside the body.

Their major advantage is that they allow fracture stabilization without large surgical incisions, making them ideal for open fractures or severe infections where internal implants may be risky. However, external fixators are less precise for fracture reduction and are unsuitable for joint fractures. Pin tract infections are also a potential complication.

Prosthetics

Prosthetics are metal or plastic devices designed to replace missing limbs following amputation. These advanced devices are often custom-made, sometimes using 3D printing.

External prosthetics are attached with straps and can be removed easily. Transcutaneous prosthetics, on the other hand, are surgically anchored directly to the bone and permanently replace the missing limb. While they have gained popularity through media exposure, they remain controversial due to potential complications. Importantly, many animals adapt extremely well to life on three limbs if the remaining limbs are healthy.

External Coaptation (Non-Surgical Stabilization)

External coaptation includes splints, casts, heavy bandages, and slings. These methods stabilize fractures without surgery, often under sedation or light anesthesia.

They are best suited for simple, stable fractures, especially in young animals. However, they are not appropriate for complex fractures and may lead to complications such as swelling, misalignment, pressure sores, muscle atrophy, or splint slippage.

How Does a Veterinary Orthopedic Surgeon Repair a Broken Bone?

Imagine a common scenario: your dog slips out of its leash and is hit by a car. You suspect a broken leg. Fortunately, the driver stops and takes you to a veterinary clinic.

The first step is always a primary assessment. While a broken leg is painful, it is rarely life-threatening unless there is severe bleeding. The veterinarian will check breathing, heart rate, pulse, temperature, and neurological status, and may perform emergency imaging or blood tests to rule out internal injuries. Pain relief and sedation are provided immediately.

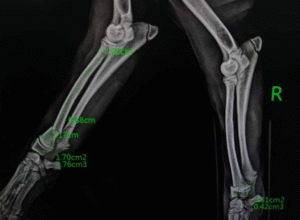

Once stabilized, attention turns to the limb. X-rays—taken from multiple angles—reveal a simple, closed, oblique fracture of the tibial shaft, with a similar fracture of the fibula. A CT scan may also be performed if available.

The veterinarian recommends surgical repair. Depending on the fracture type, specialized implants may need to be ordered, and surgery may be delayed for a few days while the dog rests and receives pain management.

Surgical Repair Using Bone Plates and Screws

On surgery day, the procedure is explained in detail. After premedication and general anesthesia, the leg is shaved and surgically prepared.

The surgeon exposes the tibia by carefully separating skin and muscle. A properly sized bone plate is selected, contoured to fit the bone, and positioned across the fracture. Screw holes are drilled, and screws—including a lag screw—are placed to secure the bone fragments. The fibula, being non–weight-bearing, is left to heal naturally.

Muscles and skin are sutured, and postoperative X-rays confirm correct implant placement.

Postoperative Recovery and Follow-Up

In the days following surgery, the incision is monitored, pain medication is continued, and strict rest is enforced. Follow-up visits allow gradual increases in activity.

After about one month, repeat X-rays confirm stable implants and progressive bone healing. Once healing is complete, implants typically remain in place unless complications occur. Physical therapy or hydrotherapy may be recommended to rebuild muscle strength and restore normal function.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is the property of Hernoda Medical Co., Ltd.

The medical education information provided is for reference and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The content may not reflect the most current medical research or clinical practices. Users assume full responsibility for any actions taken based on this information. Always consult a qualified veterinary professional before making decisions related to animal health.